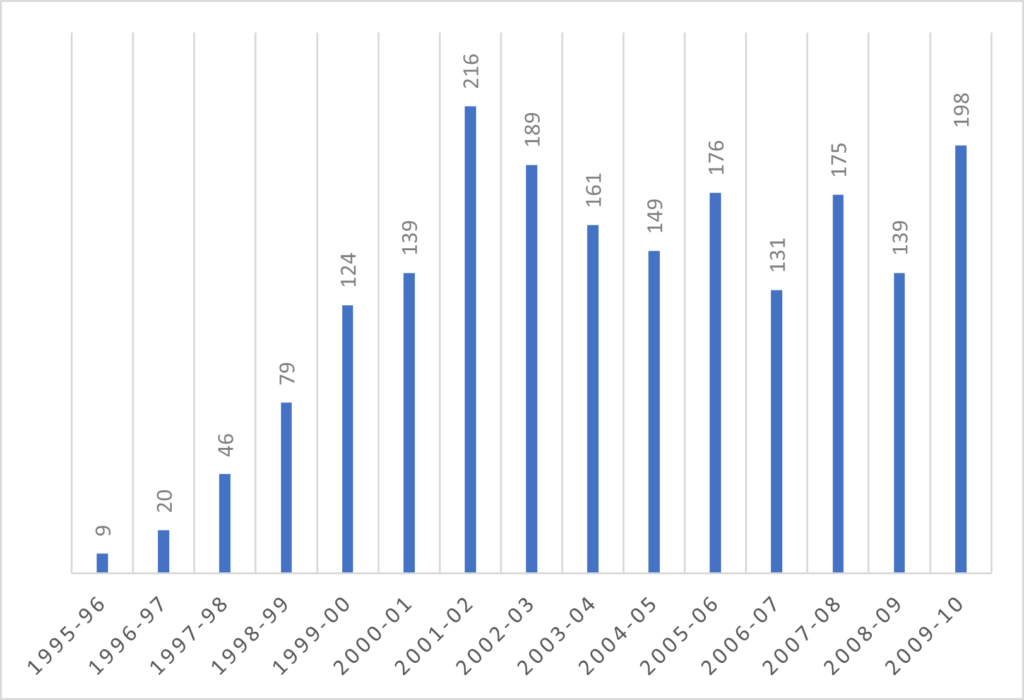

The number of quads and skaters doing them started to rise very quickly in the late 1990s and the development continued until the 2002–03 season. The International Skating Union (ISU) had possibly enabled that – the decision to allow quadruple jumps in the short program can be regarded as a conscious action towards encounraging jump difficulty. The biggest change so far was yet to come, though.

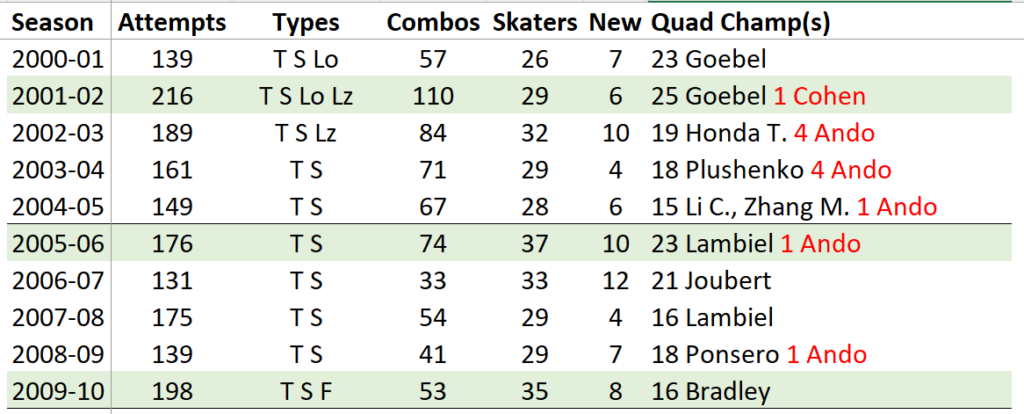

The Olympic season 2001–02 produced the highest number of quads ever: 216 attempts by 29 skaters. The quadruple loop was attempted for the first time in competition by Roman Serov (RUS) in the season before at Skate America and he continued to try in 2001–02 (no ratified jumps though). The quad Lutz also re-emerged with Evgeni Plushenko (RUS) and Michael Weiss (USA) attempting it for a little while. There were also more skaters than ever – six – attempting to master having two different quads in competition. (As before, the links embedded in the skater names lead to their Wikipedia pages.)

Then the International Judging System (IJS) happened.

Jumps and How to Judge Them

The 2002 Olympics were the incentive to make one of the biggest changes in figure skating for a very long time (the judging scandal has resulted in books and documentaries, a summary on a Wikipedia page). The 6.0 judging system had been used for decades with all kinds of variations. Its last version proved to be vulnerable to vote manipulation which led to an almost complete overhaul of the whole judging system. The International Judging System saw action for the first time in the fall of 2003 and has been in use (with all kinds of variations) since then.

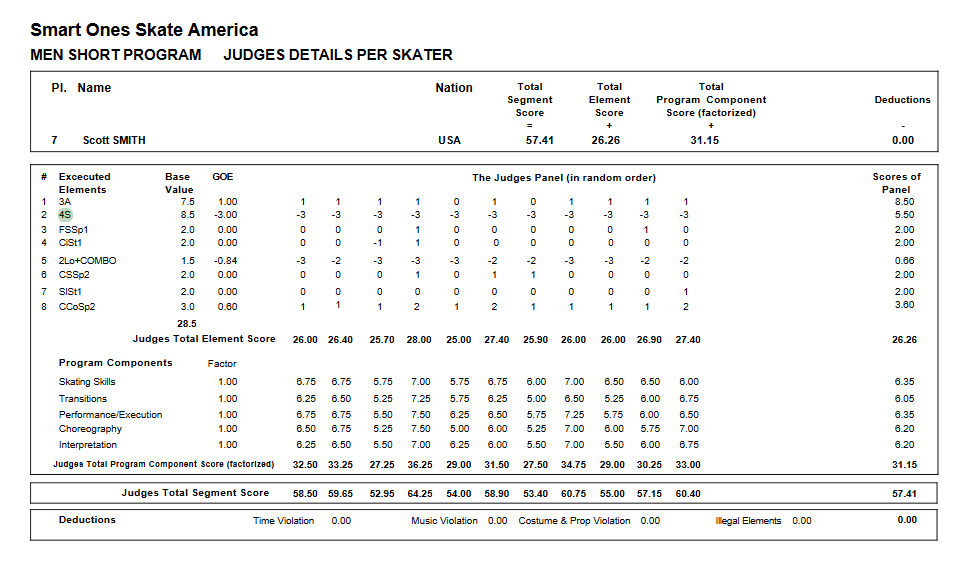

The new system continued to divide the scores into technical and artistic parts, but the greatest novelty was giving marks to every single element. And the entire score came in a detailed listing for everyone to see. There had of course been guidelines on how to make deductions from the 6.0 maximum for technical errors, but it was difficult to know whether or how the judge had applied the rules just based on the single score given. Under the IJS, the judging panel also gives dozens of marks for one skater and thus it is probably slightly more difficult for one or two judges to manipulate the results. (For a clear and concise guide on how to read an IJS score sheet, see for example the one on the So You Want to Watch FS website.)

In the IJS system, each jump is awarded a base value (BV) and the more difficult the jump, the higher the value (the order from easy to difficult is toe loop, Salchow, loop, flip, Lutz, Axel). During the performance, a Technical Panel determines what the jump is and whether there are any major erros, such as underroations or wrong edges. The Judging Panel evaluates each element by giving it a Grade of Execution (GOE), which has mostly been between -3 and +3. There are mandatory dedcutions for falls which have usually automatically earned the lowest GOE. The final score is the sum of the BV and the average of the GOEs (the lowest and highest are discarded).

For quads, the early IJS until 2010–11 meant almost a return to the situation before 1996–97. The relative tolerance for risk-taking and mistakes seemingly applied in the previous seasons vanished and mistakes in jumps were punished rather harshly. For example, the most common quad, the toe loop, had the base value of 8,00 in the 2003–04 season and the best quality 4T could earn 11,00 points with a +3,00 GOE. However, mistakes could make that big score disappear very quickly. The jumps were under a new kind of scrutiny by the Technical Panel and for example, an underrotation meant that the BV went down to 4,50 and the GOE was most often -3,00 – what could have been 11,00 points could end up as just 1,50.

The BVs of the quads were raised slightly already in 2004–05 and again in 2008–09. But although the potential scores were higher and higher, the quads did become any more common – the punishments for mistakes continued to be hard. In 2008–09 and 2009–10, the higher BV was counteracted by factored negative GOEs: -3 became -4,80, -2 -2,40, and -1 -1,20. During that period no one got the highest GOE (+3,00) – the best GOE was +2,67 and it was awarded once – but 67 jumps got the lowest GOE score -4,80. It was (and still is) much easier to get the lowest GOE than the highest.

The Quiet of the Early IJS Quad Scene

When the results could be decided by tiniest of margins in the scores (0,01 points is enough) and most of the top men were doing very similar elements technically, it was very quickly deemed to be wise to be very, very cautious. Consequently, quads tended to be attempted by those who were most consistent with them. The kind of experimentation and boundary stretching seen between 1996–97 and 2002–03 vanished for almost a decade.

Caution meant that from 2003–04 until the World Championships in 2010, only 4Ts and 4Ss were attempted in competition. Even the 4S became almost a rarity with less than 20 attempts per seasonin average. Only one or two skaters per season dared to attempt both jumps. The seasonal jump totals went back to the levels of the late 1990s and stayed there (see the chart above). The number of quadsters per season was 31 on average.

Starting from the 2010–11 season, the jump scoring was changed to encourage more risk-taking. An underrotated quad would earn at least the same or even a slightly higher score than the same triple could. The proportions of underroated or downgraded jumps before and after the scoring adjustment shown in the table below indicate how the early IJS harshness limited quad attempts.

| Seasons | Jumps | < / << Jumps | % of All Jumps |

| 2003-10 | 999 | 105 | 11% |

| 2010-20 | 7483 | 2050 | 27% |

Under the early IJS rules, it was better to do a clean 3T or 3S than attempt a poor quality 4T or 4S, but that changed in the 2010s.

Quad Statistics for the 2000s

Despite the harsh judging and moderate risk-taking, quads had become an important part of a top skater’s element repertoire and they did not go away. A total of 74 skaters started to jump quads in the 2000s – twice the numbers for the 1990s (37).

The seasonal basic data is presented in the table below. Combos mean quads in combination, New refers to the number of skater attempting quads for the first time that season. The last column lists the highest seasonal jump counts for men and women (with red). The green highlight marks the Olympic seasons.

The importance of the quad can also be seen in a new data source. The ISU started to publish seasonal World Standings/Rankings of skaters in the 2001–02 season. Until the 2006–07 season, the published list covered usually only 15 to 30 skaters, but after that it is possible to check how many of the skaters in the Top 30 or Top 100 in the world had attempted a quad in competition at least once during their careers. Almost all the Top 30 men were regular quadsters by the end of the 2000s, and of the Top 100, 60% to 67% had attempted quads.

The top quad attempt counts per skater per season were often below 20, but it is somewhat amusing to note that in the 2005–06 season the Quad King with 23 attempts was Stephane Lambiel (SUI) who is most well-known for his artistry (and he repeated this feat in the 2007–08 season). Another skater perhaps better known for his artistry, Daisuke Takahashi (JPN), was the first to attempt the 4F in the 2009–10 season. Technical and artistic excellence often go hand in hand in figure skating.

The 2000s saw the first skaters with 100 quads in international competition. Evgeni Plushenko and Li Chengjiang (CHN) were the first to achieve this in the mid- and late-2000s (see the post on the 1990s) – both had started attempting quads in the 1990s. Brian Joubert (FRA) started his quadster career in 2001 and got to 100 internationally in the fall of 2013 ending his career with 134 attempts.

Three other skaters started in the latter part of the decade and got to 100 before retiring: Sergei Voronov (RUS) 116 from 2006 to 2019, Konstantin Menshov (RUS) 105 from 2007 to 2015, and Alexei Bychenko (ISR) 123 from 2008 to 2022. All these skaters relied mainly on the 4T with occasionally trying other types of quads (usually 4S).

Those jump totals might sound huge, but they are still far away from what Kevin Reynolds (CAN) did: first quad attempt in competition in 2005 and total of 167 in international competition by his retirement in 2019. Javier Fernandez (ESP) got 162 quad attempts between 2009 and 2019. Both Reynolds and Fernandez were among the first to jump both 4T and 4S regularly.

Comparing Quad Quality

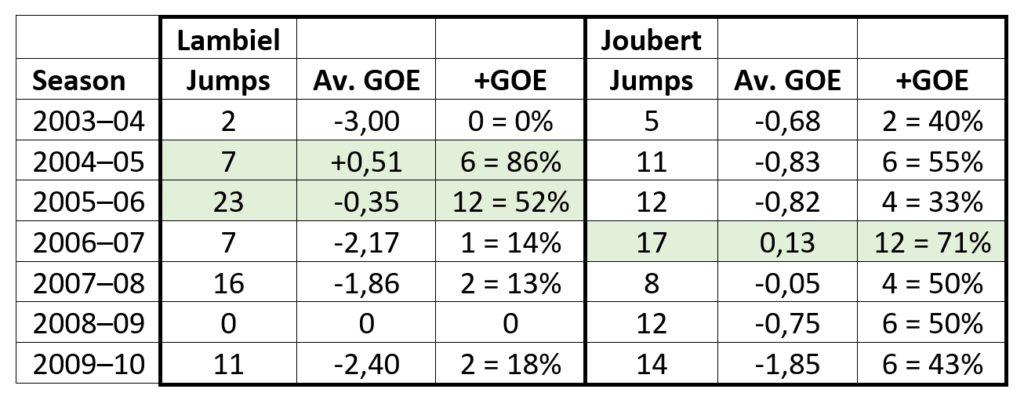

The information on the detailed IJS score sheets makes it possible to calculate all kinds of statistics. For the first time, it is possible to compare the quality of the jumps quantitatively. For example, Stephane Lambiel was the Quad King twice and attempted all his 75 quads in the 2000s. Most of them (66) took place in the IJS era with detailed data available on them.

He only had the 4T but could do it in combination, usually with a 2T or a 3T, but also with two doubles which was the fashion at the time. His program quad layout was regularly 1+2. Only four of his quads were deemed underrotated.

The quality of his jumps is indicated by two metrics: average GOE and the proportion of quads with positive GOEs among all his attempts. The average GOEs tend to be very low as it is easier to get a low score than a high one. During the early IJS, the average GOE for all the 999 jumps is -1,44 and Lambiel’s is -1,24 which is a good result.

The second metric for the whole period is 340 jumps with a GOE 0,00 or above, that is 34% out of the 999 attempts from 2003 to 2010. Considering that the average GOE is negative (-1,44), a jump with just the BV and GOE 0,00 is already quite a good one. Lambiel had 23 such jumps out of 66 or 35% showing that he did not have particularly many very good jumps compared to the rest of the field.

Lambiel’s seasonal data is shown in the table below. The seasons 2004–05 and 2005–06 are clearly his best jumping years (with green highlight). These were also the seasons when he won his two World Championships.

As a comparison, the same data is presented for Brian Joubert on the right side of the table. Joubert also attempted only 4Ts and got 79 of them under the early IJS. His average GOE is -0,70 and the proportion of +GOE jumps is 51% (40 out of 79). His jumps were overall of higher quality than Lambiel’s. Joubert’s best quad year was 2006–07 (marked with green highlight), which also in his case was the year he won the World Championship.

For the entire decade most skaters had only one type of quad in their repertoire – most commonly the 4T. Many of them could also do it in combination which meant that they could jump one quad in the short and two in the free. Those few who had two different quads could add one more to their free, but during the 2000s only five skaters could do this: Timothy Goebel (USA), Takeshi Honda (JPN), Brian Joubert, Emanuel Sandhu (CAN), and Zhang Min (CHN). Perhaps not surprisingly, there were only two attempts of SP+FS 1+3 layout during the early IJS (Joubert and Zhang Min).

Women in the 2000s

The quick development of the early 2000s also inspired some women. Sasha Cohen (USA) went for a 4S at the 2001 Finlandia Trophy. About a year later, Miki Ando (JPN) got the first landed 4S by a junior woman at the Junior Grand Prix Final. Ando continued to try 4Ss until 2008 but did not manage a clean one again. Her career total was 11 attempts.

Kimmie Meissner (USA) and Joannie Rochette (CAN) have both stated they trained quads, but neither attempted one in competition.

It was probably enough for most women to try and manage triple–triples in the harsh judging environment of the early IJS without wanting to go for quads.

Conclusions

Seeing the development (or lack of it) in the 2000s, it is not very surprising that the 2010 Olympic event was won without a quad. Evan Lysacek (USA) did have a 4T (with 15 attempts internationally), but none of his rivals were capable of producing outstanding technical difficulty with quads. Ten skaters did quads in Vancouver and only Stephane Lambiel had a SP+FS 1+2 quad layout. (Among the other top competitors, Plushenko did 1+1 and Takahashi 0+1.)

The risk of trying quads and making mistakes in them did not really pay off for any of the skaters in the end. That was really the story of quads during the early IJS in a nutshell. (This result was discussed widely in the media as shown by the Wikipedia page dedicated to it.)

It is a popular belief among figure skating fans that the IJS would encourage jumping above anything else. However, the results of the quads analysis presented above indicate quite the opposite. The early IJS was a bit like the 6.0 system with its requirement of perfection (that could be reached only very rarely), merely expressed differently. The rapid development of the quads at the turn of the millennium halted immediately when the new judging system was applied.

But the IJS can also be used in the opposite manner as will be seen in the story of the 2010s.

Want to know more?

Read the previous posts related to the dreamers of the pre-1980s, the beginnings of the quad in the 1980s and the leaps and bounds of the 1990s. The post on Making of gives additional background on sources and data collection among other things.

One thought on “The Age of Stagnation: The Early IJS from 2003 to 2010”